Thermo and Fluid Sciences Review

A brief review of thermodynamics.

The Laws

Before discussing the 0th, 1st, and 2nd laws, it is important to acknowledge the existence of a relation betweeen the properties of state. This is sometimes referred to as the 00 law. Behold the equation of state

0

The zeroth law states that two systems in thermal equilibrium with a third are in thermal equilbrium with each other.

1

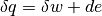

The first law of thermodynamics deals with the conservation of energy and can be stated in a variety of ways. The simplest statement for a closed system is by far

where  is the heat transferred into the system, and

is the heat transferred into the system, and  is the work transferred from the system.

is the work transferred from the system.

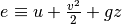

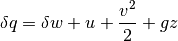

On a unit mass basis, one can also say

We take special care to note  and

and  as inexact differentials, or path dependent, while

as inexact differentials, or path dependent, while  is an exact differential and represents the change only between an initial and final state.

is an exact differential and represents the change only between an initial and final state.

We can continue to expand the expression for the first law knowing that  and say

and say

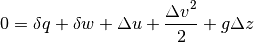

Finally we arrive at

All the equations above are different ways to say the same fundamental thing - energy is conserved. Heat and work are two types of energy in transit, heat being the transfer of energy due to a temperature gradient (and always from the higher temperature system to the lower), and work being the effect of elevating a mass in a gravity field.

2

The second law of thermodynamics points to the very direction of all processes in our universe. Carnot, Clausius, and Lord Kelvin all came to this significant conclusion while working to understand things like steam engines and machines. Kelvin and Planck stated that it is impossible for an engine operating in a cycle to produce net work when exchanging heat with only one temperature source. In laymans terms, this can be thought as a machine using energy from a thermal reservoir cannot operate unless there is another, lower, thermal reservoir.

Clausius determined that heat can never pass from a cold body to a warmer body without the aid of an external process, giving recognition of the irreversibility of certain processes such as fluid friction and heat transfer. All real processes are irreversible. For a fictitious reversible process, we can quantify this degredation of energy quality by defining entropy.

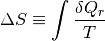

This defines a change in entropy in terms of a reversible addition of heat  (which we know is an impossible process) for a system temperature. We can write the definition of entropy as such because entropy is a state, and is independent of the process. Regardless, it may be more prudent to write the definition of entropy as

(which we know is an impossible process) for a system temperature. We can write the definition of entropy as such because entropy is a state, and is independent of the process. Regardless, it may be more prudent to write the definition of entropy as

or

Where the first expression shows we understand that we are always trending towards greater entropy, and the second stating that the change in entropy is the heat we add in addition to irreversible contributions from friction, viscosity, thermal conductivity, and so on.

Property Relations, Entropy, and Perfect Gases

Enthalpy is defined as the specific internal energy of a system and the product of pressure and volume, or the sum of thermal energy and “flow work”.

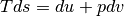

Recalling our definition of work and our definition entropy on a unit mass basis for a reversible system.

we can come to the result

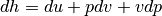

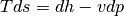

We can further manipulate this result by differentiating the definition of enthalpy and replacing the  term.

term.

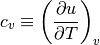

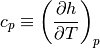

When it comes to perfect gases (substances that follow the perfect gas equation of state), specific heat at constant volume and specific heat at constant pressure are defined as follows:

Since both of these are functions of temperature only, we can lose the partial derivative.

An very common term used in gas dynamics is the ratio of specific heats

can be thought of the ratio of the fluids specific internal energy and pressure volume ability’s to take or remove heat away from a system to just the internal energy’s ability to do so.

can be thought of the ratio of the fluids specific internal energy and pressure volume ability’s to take or remove heat away from a system to just the internal energy’s ability to do so.

The Liquid Vapor Dome

Example Derivations

Pumps

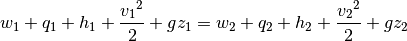

The energy equation is a great way to understand pumps and their operation.

We can then multiply through by  , and remove the terms for heat in, heat out, and work out. The work is being imparted to our fluid and heat in and out are negligent compared to the other forms of energy in this process.

, and remove the terms for heat in, heat out, and work out. The work is being imparted to our fluid and heat in and out are negligent compared to the other forms of energy in this process.

![W = \dot{m} \left[ \left( h_1 + \frac{{v_1}^2} {2} + gz_1 \right) - \left( h_2 + \frac{{v_2}^2} {2} + gz_2 \right) \right]](../_images/math/83e9f0d858fcdd0f9e7a62282720dd3e13d24cb3.png)

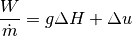

We know that enthalpy is defined as  , and we rearrange to solve for the common “pump head” equation.

, and we rearrange to solve for the common “pump head” equation.

where  is the shaft power,

is the shaft power,  is specific internal energy, and

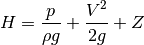

is specific internal energy, and  is known as the pump head, defined as

is known as the pump head, defined as

Of course there will probably be losses in our system, such as the marginal increase of heat imparted to the fluid to slippage from our pump, so our equation should actually read something like

The pump efficiency can then be defined as

The efficiency term can further be broken down to capture efficiency of various aspects of the pump, such as mechanical efficiency (capturing external drag from bearings and seals), hydraulic efficiency (ratio of output head to input head), and volumetric efficiency (leakage of the fluid).